Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

IC 2 DC -- Planning meeting tonight

ORGANIZATIONAL MEETING FOR BUS TRIP TO D.C. ANTI-WAR DEMONSTRATION

This is an open invitation to anyone interested in going toWashington, D.C. for a demonstration and march on Jan. 26-28 (Fri.-Sun.) sponsored by United For Peace and Justice. The UI Anti-War Committee is holding an informational meeting on Tuesday, November 28, at 6:00 pm in Meeting Room B of the Iowa City Public Library. The two main goals of the meeting are to give basic information about the trip for anyone interested in going and to find volunteers who are willing to organize and coordinate the trip. If you are interested in going, and you want to help to make this a great experience for all involved, please come and bring a friend. We will need plenty of help.

Again, the initial meeting is Tuesday night, Nov. 28, at 6 pm in Meeting Room B of the Iowa City Public Library. Please feel free to attend and to spread the word about this most important event in pressing the anti-war movement's case against the War in Iraq. Also, forward this e-mail to anyone you know who might be interested.

Sincerely,UI Antiwar Committee

Individuals with disabilities are encouraged to attend all University of Iowasponsored events. If you are a person with a disability who requires anaccommodation in order to participate in this program, please contact Tim inadvance at 319-936-2307 or send an email to uiantiwar@riseup.net.

University of Iowa Antiwar Committee

www.uiantiwar.org

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

"The world changed after 9/11...."

But not *right* after.

*Right* after, for a period of a couple weeks, people were gentle and courteous to each other to an extent I had never witnessed in my life. Close to how they behaved during the Midwest floods of 1993, but generous less with their physical activity and more with their compassion on each other's behalf. The outpouring of money for the victims was probably as great as during the flood; the outpouring of blood as people lined up to donate had to have been greater.

At work on 9/11, there was something unspoken that I sensed strongly: you didn't know who around you might have been affected--which clients, which coworkers' relatives--so you treated everyone with kindess and consideration. Going home from work that day, as a relatively new driver, I noticed the complete absence of road rage and road rudeness. People drove slowly, used signals, waved you in. We all knew how the other guy felt--certainly no better than we did ourselves, and possibly--god forbid that he should have a relative that felt those buildings shake--possibly much worse.

A friend somehow was on the list to get tickets to the Oprah show just at that time, and just happened to get them for her first show of that season, which suddenly became a show about 9/11. The friend couldn't go, and I didn't want to try driving my inexperienced self to Chicago, so I took the Greyhound.

Coming through Iowa City from the West Coast, the bus stopped at Walcott so the passengers could get something to eat. I'd just boarded the bus an hour before, so I remained on board, watching other buses come and go and watching people who were watching still others--those others being half a dozen Muslim men just outside my window, dressed in traditional clothing, carrying prayer rugs, and conferring, it seemed, about the direction they needed to face. Iowans watched, Midwesterners watched, their fellow Americans watched, white people watched, warily, from the sidewalk.

I watched with growing concern. What if the men were harassed? Attacked, even? It was September 16, 2001, and not a week had passed, and we were at a truck stop in Iowa. If those onlookers made a move toward the Muslims--if I saw one of them even speak with an unkind expression on his face--I would have to get off the bus and defend the praying men.

The last lingering effect of my halfhearted Catholic upbringing is a guilty conscience over sins of omission. It's not just what you do that you shouldn't have done that can get you in trouble. It's also what you don't do that you should have. In my life up to that point I'd not done some of those things, and they were and are some of my most regular 3 a.m. visitors.

So if anything happened, if anyone threatened, I would have to respond, defend, take a stand. I watched the men lay out their prayer rugs in an empty space in the parking lot, and I watched them kneel and bow, and most of all I watched the watchers. And I saw...nothing. Nothing harmful, nothing even unkind. Curiosity on a few faces of middle-aged white men in John Deere caps. Sadness, or merely solemnity on other faces. Even respect, I think, on a few. And tears on mine, as I thanked a god I didn't believe in for the country whose government I routinely criticized.

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/traveloutdoors/2003442495_imams22.html

"The imams were removed from the flight to Phoenix on Monday night after three of them said their normal evening prayers in the terminal in Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport before boarding."

The world changed after 9/11. But not right after.

Monday, November 20, 2006

My choice

Everyone picks their battles. Recently I've been more focused on international peace issues, but there was a time when I was very active in local abortion-rights groups and actions and of course I'm still interested in the issue and strongly pro-choice.

So, since I moved to the west side of town and would pass by Planned Parenthood on my way to work--actually, on my way to get drive-through coffee that I often need in order to *get* to work--I felt a little sheepish at the occasional sight of men carrying anti-choice signs. I should stop, I would think. I should try to stop them.

Last week, they were out picketing again, but this time there were two police cars and a parking lot full of clinic clients' cars. The cops were talking to one of the picketers. The other one was shouting at people as they entered the clinic.

Because the situation looked more serious than usual, I almost did stop. Then I reluctantly decided against it and went on to get my coffee. But when I'd done that, I found myself turning the car back toward the clinic. A woman's prerogative.

I drove into the clinic parking lot, got out of my car, and went in. An older man stopped me just inside. I told him that I wanted to make a donation. He smiled broadly and said, "Okay!" I went in and wrote my check. (Which the embattled clinic staff seemed disproportionately grateful for at the time; I received an extremely prompt thank-you note later in the week.)

I've long had some political qualms about the pledge-a-picketer strategy for clinic defense, but it was the choice I had time for that day. As I drove out of the parking lot, I rolled down the window and politely told the shouting anti-choice man that I would write a check whenever I saw him picketing. He--not quite so politely--told me that I was going to hell. Maybe, I agreed, but first I was going to work.

What was left out of the "cartoon controversy"

Cartoons of the prophet Muhammad in a Danish newspaper were discussed again on NPR this morning, and once again, the "liberal media" failed to mention that before publishing those inflammatory cartoons the same newspaper had refused to publish satirical cartoons depicting Christ. Christians don't have the same prohibition against depicting religious figures that Muslims do, and the West is "tolerant" of satire and encouraging of free speech...so what gives?

Human shield deters Israeli strike (BBC 19 Nov 06)

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/6162494.stm

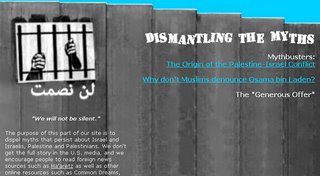

Where is the Palestinian Gandhi? Where is their Nelson Mandela? Google nonviolent Palestinian resistance and get some information we don't hear about in the U.S. media. While you're at it, google Israeli peace movement and get another shock--there is one. In fact, read Ha'aretz (www.haaretz.com) for more public debate and more criticism of Israeli government policy than we're ever exposed to in the country that funds that policy.

Friday, November 17, 2006

Single issue

In 1980, Ronald Reagan and Jimmy Carter presented a marked contrast in most voters' minds. Not in mine. At 19 years old, registered as a Republican and preparing to vote for the first time, my single issue was the re-establishment of draft registration. The two major-party candidates were both for. I was most decidedly against.

Too young to experience the 1960s, I was still old enough to remember the latter part of that decade. I remembered watching the strange shape of Vietnam over the anchorman's shoulder, the line shifting, the numbers changing. So many of us, so many of them. So many of us, so many of them. So very many of us--and so many, many more of them.

I also vividly remembered the 1960s' sense--now sadly lost to most of the middleaged and older, and never present in the lives of those who are younger--that another world was possible. We could arrange our lives very differently from what we'd been told. Blacks and women and the poor and gays and lesbians and people from other countries could be embraced as the equals of rich white American men. Compassion, cooperation, tolerance, and dialogue could prevail over competition, bigotry, and war. We could make it all happen. It was our responsibility to do so.

That's what brought me out into the Indiana summer heat in 1980, carrying pen and clipboard and my first of many bags of "lit"--independent candidate John Anderson's campaign literature. Anderson was against draft registration, and he needed 7500 registered voters' signatures to get on the ballot in Indiana after he lost the race for the Republican nomination. That's about the sum total of what I knew about him, but it was enough to motivate me to get my one percent of those signatures, no matter how long it took or how much hostility I encountered.

Some of that hostility came from my own dad, who mystified me by refusing to sign Anderson's petition. Surely, I thought, even if he doesn't like the guy's politics and would never vote for him, he should understand and support his right to be on the ballot.

I had more faith in my dad's objectivity and principles than they deserved. My parents had started secretly opening my mail, and some of it was from the CCCO (www.objector.org). I wasn't a member, but--given my single issue--I was interested. My parents, to be fair, were scared. They remembered Joseph McCarthy and the era of the blacklist. A connection to an organization of conscientious objectors could ruin my life. The government might target me.

I thought if that's really the case--if my government would deny me that basic right guaranteed to me by the First Amendment--well then, all the more reason--all the more *obligation*--to oppose such a government. I finished collecting my signatures, John Anderson got on the ballot in Indiana, and I voted for him. But I was on my way to leaving electoralism behind.

In a way I'm still a single-issue voter, although now I vote far more often with my feet as an activist than with my hand in the voting booth. My single issue now is social justice in all its forms and every context, and that election--that choice to get involved and do your part--is always going on. Another world *is* possible. Take it from someone who got a glimpse of it that she can never forget.

Another Vietnam?

Noam Chomsky says no, but his reasons are no cause for comfort or complacency among those opposed to the war in Iraq, or those who hope that the Democrats who voted for it will end it.

Iraq is not another Vietnam because in Vietnam the stakes for the U.S. were more purely ideological, rather than economic or even strategic. It was a loss that the U.S. ruling class could much more easily (though of course not happily) sustain.

Iraq, by contrast, has large and easily accessed reserves of capitalism's life-blood. It is located in the oil-rich heart of a region that the U.S. wants to control not only (perhaps not even primarily) to ensure its own access to oil, but also to ensure its control over its competitors' access.

Capitalism is about competition. Economic competition with Europe and rising superpowers like China easily shades over into international trade disputes and military conflict over markets and resources. In Iraq and in U.S. and Israeli plans to re-shape the Middle East, the U.S. is trying to establish a stranglehold not just on Arabs and Muslims whose resources it needs, but also on its world competitors, whose market share of the earth it covets.

Dream on, voters, if you think that the situation or prospects for peace really changed on November 7. Your government is building giant military bases in Iraq--the kind that neither party is building with the intent to abandon them.

Another Vietnam....If only it were. The challenge then for antiwar activists might be less daunting.

The Mideast matters to the Midwest

I’ve frequently had to explain to family, friends, and coworkers why I’m so interested in the Middle East, especially Israel and Palestine. I’m an Irish-English-German-and-Dutch American mongrel, with a lapsed half-Catholic background and no family ties to Arab or Muslim people. I grew up in a fundamentalist Protestant town among the casually anti-Semitic, for whom it was natural to talk about how they had “Jewed someone down” on the price of something. Most of these people had never known a Jew, and neither did I until I went to college.

College and graduate school, however, opened my eyes to the world outside the Midwest. I had been interested in politics since I was ten or eleven, and became an activist in electoral politics as soon as I could vote. But during my time at the UI, especially, I met people outside the classroom who educated me about issues and political positions outside of what I’d heard in the media and outside the party lines of the Democrats and Republicans. I was radicalized by these people—most of them socialists, some of them Jewish, and a Palestinian fellow grad student named Saed Abu Hijleh.

I was one of a large number of people who knew Saed during his time at the UI. He was unusually courteous yet warm and instantly likeable. He was a member of the General Union of Palestine Students while he was at the UI and I met him through my own involvement with Operation U.S. Out, which organized against the first Gulf War in Iraq. During that time, GUPS permanently raised the level of local awareness about the Israel-Palestine conflict. By the time Saed graduated and returned to Nablus in the West Bank, he and other GUPS members had influenced many of us to continue to educate ourselves and others about the plight of Palestinians in their Israeli-occupied country.

Because of my acquaintance with GUPS, I was involved in People for Justice in Palestine very early in its history as a local activist group, first on campus and later in the broader community. But my involvement at first was a relatively small part of my general commitment to left activism. Then as now, I felt that a just solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict was critical to international peace, but Palestine was only one of several focuses for me, and PJP was not at the very top of my list of priorities.

That changed in the fall of 2002. A Palestinian woman had been murdered and her husband and son injured by the IDF while she sat on her front porch embroidering, and PJP was trying to raise awareness about the case. Only when I finally heard the son’s first name did I realize that my friend’s mother—a lifelong activist for peace and justice—had been shot to death in front of him. And only then—thinking of my own mother, her meticulously careful embroidery that had inspired my creativity, her infinitely greater care for others’ comfort and feelings, and the terror and grief I felt just a few years before when she had been seriously ill—only then did the terrible injustice suffered by my friend’s people come home to me, to my very heart.

The murder of Shaden Abu Hijleh, whose four children had graduated from the UI, was not widely noticed here beyond the circles that GUPS and PJP were able to reach. Local media barely mentioned it. The UI Alumni Association wouldn’t touch the story. Clearly, I thought, it was a story—and a side of a much larger story—that needed to be heard.

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Covering an issue

The "issue" of whether or not to permit Muslim women living in Western cultures to wear the hejab has been raised recently in France, Britain, and the U.S., but it is a false one that encourages anti-Muslim discrimination. You can talk all you want about Muslims needing to adapt to the cultures they volunteer to become a part of...but to what standard are we asking them to adapt? Paris Hilton's? That of the Amish or Mennonites? Yours, mine, or some universal dress code devised by Congress? And since when do the self-described tolerant cultures of the West require anyone to dress *less* modestly than their morals and personal taste dictate?

I'm not a Muslim and I understand that the hejab can be a symbol of a patriarchal culture forced on some Muslim women as a means of control. But I also understand that "to cover or not to cover" is a deeply personal choice that other Muslim women make freely. I don't believe that we have the right to enforce one choice or the other, and I do think that the attempt to do so will actually be experienced by Muslims--both women and men--as religious persecution, resulting in alienation from rather than acceptance of or adaptation to Western culture.

The clothing that other individuals choose to wear, whatever reasons they have for their choice, does not cause me any harm. And in cases where public safety *is* concerned--as in Florida, where police want driver's licenses to show drivers' full faces--I can imagine ways to accommodate the needs of both traditionally dressed Muslim women and legitimate state interests.

If the American experiment has tried to prove anything, it is the proposition that people from different cultures can live side by side, free to practice their own religions but not to force others to do so. Abandoning that ideal is far more damaging to my freedom--as a person and as a woman--than my Muslim sisters' head scarves ever could be.